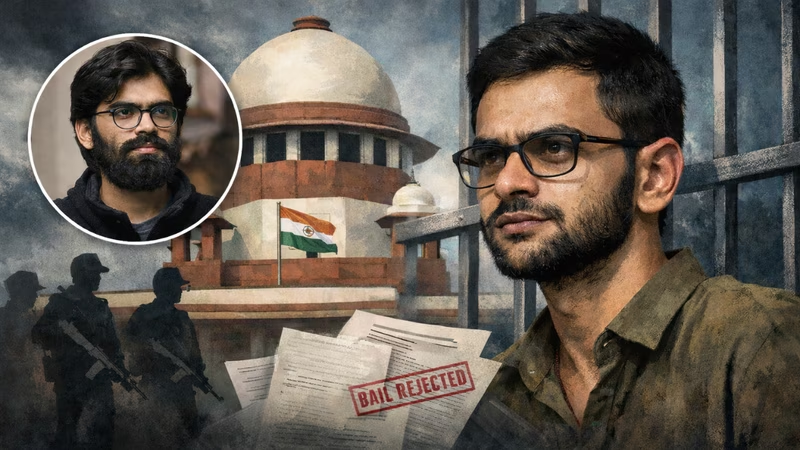

In a courtroom decision that has reignited a fierce national debate, the Supreme Court of India on January 5, 2026, denied bail to student activists Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam . The ruling wasn’t just a procedural denial; it was a stark declaration of their alleged role in the 2020 Delhi riots conspiracy—as the “ideological drivers” behind the violence . While five of their co-accused walked free on bail, Khalid and Imam remain incarcerated, trapped in the legal quicksand of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, or UAPA. This case is a masterclass in why UAPA bail remains one of the most elusive concepts in Indian jurisprudence.

The court’s distinction between “planners” and “facilitators” has profound implications for civil liberties and the future of dissent in the country. So, what makes the UAPA so powerful, and why does it treat some accused so differently from others?

Table of Contents

- The Supreme Court Ruling: A Hierarchy of Culpability

- What is the UAPA and Why is Bail So Hard?

- Section 43D(5): The Legal Wall Blocking UAPA Bail

- Who Are the ‘Ideological Drivers’?

- A Comparison of Fates: Inside the Delhi Riots Case

- Conclusion: The Chilling Precedent of Umar Khalid’s Case

- Sources

The Supreme Court Ruling: A Hierarchy of Culpability

The core of the Supreme Court’s judgment lies in its creation of a “hierarchy of culpability” within the larger conspiracy alleged in the Delhi riots case . The bench, led by Justices, concluded that while some accused played peripheral roles—perhaps providing logistical support or being present at certain meetings—Khalid and Imam were central to the very conception of the alleged plot .

The court stated that the evidence on record suggested they were not mere participants but the intellectual authors, the ones who allegedly provided the ideological framework that fueled the unrest . This distinction is critical because it moves their alleged actions from the realm of reactive protest into the domain of premeditated conspiracy—a key threshold for invoking the stringent provisions of the UAPA.

What is the UAPA and Why is Bail So Hard?

Enacted in 1967 and significantly amended over the years, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act is India’s primary anti-terrorism law . Its purpose is to prevent activities that threaten the sovereignty and integrity of India. However, its application has been widely criticized for its potential to stifle legitimate dissent.

The Act’s most notorious feature is its bail provisions. Unlike regular criminal law, where “bail is the rule, jail an exception,” the UAPA flips this principle on its head . The law creates a presumption against bail, placing an enormous burden on the accused to prove their innocence before even getting a chance to properly defend themselves outside of prison.

UAPA bail and Section 43D(5): The Legal Wall Blocking Freedom

The primary legal barrier is Section 43D(5) of the UAPA. This section states that a court shall not grant bail if, upon reviewing the case diary and other materials, it finds a “prima facie” case against the accused . This is a remarkably low threshold for the prosecution to meet.

In practice, this means:

- The court doesn’t need to be convinced of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

- It only needs to see enough in the police’s initial paperwork to believe a case might exist.

- This allows for prolonged incarceration without a trial, sometimes for years, as has been the case with Umar Khalid, who has been jailed for nearly five years without a conviction .

This provision has led to a consistent judicial pattern of denying bail under the UAPA, creating a system of de facto punishment before trial .

Who Are the ‘Ideological Drivers’?

The term “ideological drivers” used by the Supreme Court is not a standard legal phrase but a judicial characterization with heavy implications. In the context of the Delhi riots case, it refers to individuals who are alleged to have conceptualized and promoted a specific political narrative that, according to the prosecution, directly incited the violence.

For Umar Khalid, this centers on a now-infamous speech he gave at Amravati in February 2020, where he spoke about a “larger plan” of resistance against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). The prosecution argues this speech was a coded call to action. For Sharjeel Imam, it’s his inflammatory speeches that are cited as evidence of his role in sowing discord . The court’s acceptance of this narrative as a basis for denying bail sets a dangerous precedent where the content of one’s speech can be grounds for indefinite detention under a terror law.

A Comparison of Fates: Inside the Delhi Riots Case

The starkest illustration of the court’s “hierarchy” is the divergent outcomes for the accused. On the same day Khalid and Imam were denied bail, the Supreme Court granted relief to five of their co-accused: Gulfisha Fatima, Meeran Haider, Shifa-ur-Rehman, Mohd Saleem Khan, and another individual .

This split decision highlights the prosecution’s strategy and the court’s willingness to differentiate roles within a single conspiracy charge. The five granted bail were seen as having played secondary, facilitative roles, while Khalid and Imam were placed at the apex of the alleged conspiracy pyramid . This raises a critical question: at what point does organizing a protest or giving a passionate speech cross the line into becoming an “ideological driver” of terrorism under the UAPA?

Conclusion: The Chilling Precedent of Umar Khalid’s Case

The Supreme Court’s denial of UAPA bail to Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam is more than just a legal setback for two individuals. It is a watershed moment that defines the boundaries of permissible dissent in modern India. By endorsing the “ideological drivers” theory and upholding the near-impossible bail conditions of the UAPA, the court has sent a clear message about the state’s power to detain those it deems to be at the heart of a conspiracy, based on their ideas and words as much as their actions.

While the court has left the door open for them to refile their bail pleas after certain witnesses are examined , their immediate future remains behind bars. This case will undoubtedly be studied for years as a defining example of the tension between national security and fundamental rights. For a deeper look at how anti-terror laws impact civil society, see our analysis on [INTERNAL_LINK:impact-of-anti-terror-laws-on-indian-democracy].

Sources

- Live Law: Supreme Court denies bail to Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam in Delhi Riots Conspiracy Case

- Article-14: Supreme Court Judge Whose Jail-Not-Bail Ruling Has Left Umar Khalid In Prison For Five Years

- Indian Constitutional Law and Philosophy: Bail under the UAPA

- The Hindu: SC rejects bail to Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam in 2020 Delhi riots case

- Supreme Court Observer: The SC on bail under UAPA and PMLA: a dataset from 2024 to 2025