What if you came home after decades—only to find your own name on a death register?

That’s exactly what happened to Sharif Ahmed, a 62-year-old man from Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh. Declared dead by his own family and local authorities in the late 1990s, Ahmed reappeared in his ancestral village in early January 2026—not as a ghost, but as a living, breathing citizen in urgent need of paperwork. His return, after being presumed dead for 28 years, has left relatives weeping, neighbors stunned, and officials scrambling to untangle a bureaucratic nightmare that highlights a disturbing flaw in India’s civil documentation system.

Table of Contents

- The Shocking Homecoming After a 28-Year Absence

- Why He Left: The Reason Behind the Disappearance

- The Document Crisis: Why He Needed His Father’s Death Certificate

- How Can a Living Person Be Declared Dead? India’s Legal Loopholes

- The Human Cost of Bureaucratic Errors

- What Sharif’s Case Reveals About India’s Identity Infrastructure

- Conclusion: A Wake-Up Call for Civil Registration Reform

- Sources

The Shocking Homecoming After a 28-Year Absence

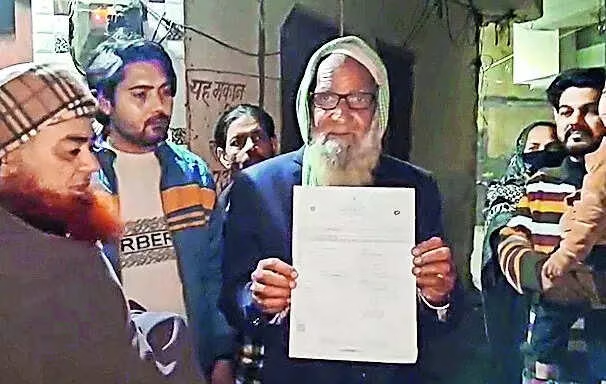

On a quiet morning in Muzaffarnagar, villagers watched in disbelief as a bearded man in simple clothes walked into the local thana (police station). “I am Sharif Ahmed,” he said. “I have not died. I am alive.”

According to police and local reports , Ahmed had migrated to West Bengal in 1997 after remarrying. With no communication for years, his family assumed he had passed away—possibly due to illness or accident. In their grief, they reportedly approached local authorities to declare him dead, a common practice in rural India to settle property or inheritance matters . His name was removed from voter lists, and his share of ancestral land was redistributed.

Now, 28 years later, he was back—not for property, but for paperwork.

Why He Left: The Reason Behind the Disappearance

There was no mystery—just life. After his first wife’s death, Sharif Ahmed remarried and moved to West Bengal to start anew. He worked menial jobs, stayed off the grid, and lost touch with his Uttar Pradesh roots. In an era before mobile phones and Aadhaar, such disconnections were tragically common, especially among low-income migrants.

“I never knew they thought I was dead,” Ahmed reportedly told officials. “I just… drifted away.”

The Document Crisis: Why He Needed His Father’s Death Certificate

Ahmed’s return wasn’t nostalgic—it was bureaucratic. He’s now settled in West Bengal and needs to get his name added to the state’s electoral roll during its ongoing revision phase. But to prove his identity and domicile, he required two key documents:

- His father’s death certificate — to establish lineage and residence in UP.

- A domicile certificate — to confirm his roots in Muzaffarnagar, which serves as proof of origin for his West Bengal application .

Ironically, to prove he’s alive and eligible to vote, he must first prove his dead father existed—a paradox only India’s fragmented documentation system could create.

How Can a Living Person Be Declared Dead? India’s Legal Loopholes

In India, a person can be legally declared dead after seven years of disappearance under Section 108 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872 . But in rural areas, this process is often informal. Families submit affidavits to local revenue or police officials, who—without rigorous verification—update records.

There’s no centralized death registry. No cross-check with Aadhaar (which didn’t exist until 2009). No automatic alerts to other states. As a result, thousands like Sharif Ahmed fall into administrative purgatory—alive in one state, dead in another.

The Ministry of Home Affairs has acknowledged this gap. In 2022, it proposed a National Death Registry, but implementation remains patchy .

The Human Cost of Bureaucratic Errors

For Sharif Ahmed, the consequences are more than procedural:

- He has no voter ID in UP or Bengal.

- He cannot access welfare schemes or open a bank account easily.

- His legal identity is in limbo—technically “dead” in his home state.

His case is not unique. In 2023, a man in Bihar was “revived” after 15 years . In 2021, a woman in Rajasthan fought for two years to prove she wasn’t her deceased sister. These aren’t anomalies—they’re symptoms of a broken system.

What Sharif’s Case Reveals About India’s Identity Infrastructure

India has made strides with Aadhaar, PAN, and voter IDs—but these systems operate in silos. A death recorded in a UP village rarely syncs with the Election Commission or UIDAI. This disconnect creates “ghost citizens” and “living ghosts” alike.

Experts argue for three urgent fixes:

- Integrate civil registration with Aadhaar: Any death declaration should trigger an automatic flag in the national ID system.

- Digitize legacy records: Millions of paper-based death and birth entries remain offline.

- Allow “identity restoration” cells: Special desks at district levels to help citizens like Ahmed reclaim their legal existence.

For deeper insights on India’s documentation challenges, see our feature on [INTERNAL_LINK:civil-registration-reforms-india].

Conclusion: A Wake-Up Call for Civil Registration Reform

Sharif Ahmed’s story is equal parts miracle and warning. His emotional reunion with weeping siblings is heartwarming—but it shouldn’t take a 28-year exile and a bureaucratic scavenger hunt to prove you’re alive. The case of a man presumed dead for 28 years is not just about one individual; it’s a mirror reflecting India’s urgent need for a unified, humane, and tech-enabled civil registration system. Until then, more citizens risk vanishing—not from life, but from the eyes of the state.

Sources

- Times of India. (2026, January 1). Presumed dead for 28 yrs, UP man returns home to collect SIR docus. Retrieved from https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/agra/presumed-dead-for-28-yrs-up-man-returns-home-to-collect-sir-docus/articleshow/126292111.cms

- Registrar General of India. (2023). Civil Registration System in India: Annual Report. Retrieved from https://censusindia.gov.in

- Indian Evidence Act, 1872. Section 108. Presumption as to absence of a person.

- Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. (2022). Proposal for National Death Registry.

- India Today. (2023, November 12). Man declared dead for 15 years returns, fights to reclaim identity. Retrieved from https://www.indiatoday.in