Table of Contents

- The Historic Day: Jana Gana Mana First Sung

- The 1911 Congress Session: Context and Controversy

- Tagore’s Response: What Did ‘Jana Gana Mana’ Really Mean?

- From Song to Anthem: The Road to 1950

- Lyrics, Structure, and Symbolism of Jana Gana Mana

- Common Misconceptions Debunked

- Why This Moment Matters Today

- Conclusion: A Song That Became a Soul

- Sources

Imagine a crisp winter morning in colonial Calcutta. The Indian National Congress is gathered for its 26th session. The air hums with debates on swaraj, unity, and resistance. Then, a voice rises—clear, melodic, and deeply resonant. It’s Sarala Devi Chowdhurani, Rabindranath Tagore’s niece, singing a new composition: ‘Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata.’ That song, later known as Jana Gana Mana, was publicly performed for the first time on **December 27, 1911**. Little did anyone know that this moment would seed India’s future national anthem—one of the most unifying symbols of the world’s largest democracy. Yet, its origins have long been clouded by myth, political speculation, and deliberate misinformation. Let’s set the record straight.

The Historic Day: Jana Gana Mana First Sung

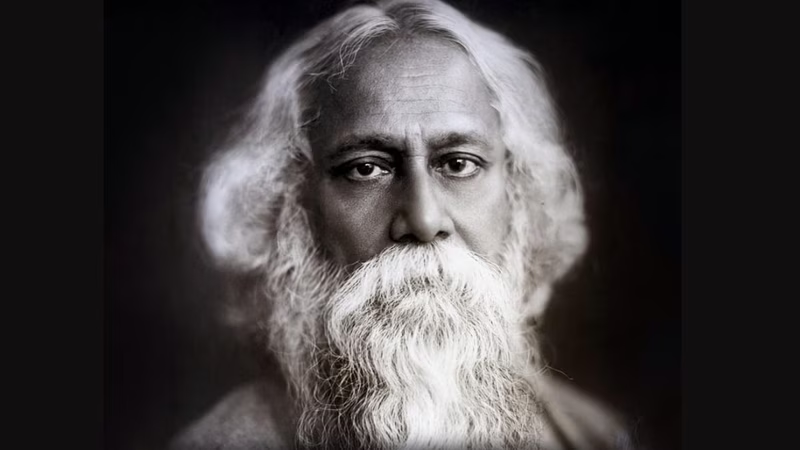

The venue was the Calcutta (now Kolkata) session of the Indian National Congress, held at the historic Ballygunge Circular Road. The session president was Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya, a towering nationalist leader. Rabindranath Tagore—already a literary giant but not yet a Nobel laureate (he’d win it in 1913)—composed the song specifically for this gathering.

It was sung not as a political statement, but as an invocation—a prayer to the “dispenser of India’s destiny.” The performance lasted just over a minute, and while it didn’t dominate headlines then, it planted a cultural seed that would flourish decades later .

The 1911 Congress Session: Context and Controversy

December 1911 was a politically charged month. Just days earlier, King George V had arrived in India for the Delhi Durbar—a grand imperial spectacle where he announced the reversal of the 1905 Partition of Bengal, a major win for Indian nationalists.

Because of this timing, a persistent myth emerged: that Tagore wrote ‘Jana Gana Mana’ to welcome or flatter the British King. Some even claimed the “Adhinayak” (leader) in the lyrics referred to George V. This theory was widely circulated during the independence movement and resurfaces even today—despite being thoroughly debunked.

In reality, the Congress session Tagore attended was a *separate* event from the Durbar. It was a nationalist platform—not a royal reception.

Tagore’s Response: What Did ‘Jana Gana Mana’ Really Mean?

Rabindranath Tagore himself addressed the controversy head-on. In a 1937 letter, he wrote: “The idea that this song was sung in praise of the British monarch is absurd… The ‘Adhinayak’ is not a human ruler but the Eternal Guide of the people” .

He clarified that the song was a spiritual ode to the divine consciousness that guides India through its diverse geographies—from Punjab to Assam, from the Vindhya mountains to the seas. The “Bharoto Bhagyo Bidhata” (Dispenser of India’s Destiny) is not a king, but a timeless, unifying force.

Tagore, a staunch critic of imperialism, would hardly pen a sycophantic tribute. In fact, he returned his knighthood in 1919 in protest of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre—a clear marker of his anti-colonial stance.

From Song to Anthem: The Road to 1950

Despite its 1911 debut, ‘Jana Gana Mana’ remained relatively obscure for decades. During the freedom struggle, ‘Vande Mataram’ was the dominant patriotic song. But post-independence, a new national identity was needed—one that was inclusive of all faiths and regions.

‘Vande Mataram,’ while powerful, had religious undertones that made some minorities uncomfortable. ‘Jana Gana Mana,’ in contrast, was secular, poetic, and geographically unifying.

On **January 24, 1950**, just days before India became a republic, the Constituent Assembly formally adopted the first stanza of ‘Jana Gana Mana’ as the **National Anthem of India**—a decision led by Jawaharlal Nehru and supported across party lines .

Lyrics, Structure, and Symbolism of Jana Gana Mana

The anthem’s first stanza—officially adopted—mentions five key regions, symbolizing India’s unity in diversity:

- Punjab (Northwest)

- Sindhu (Sindh, now in Pakistan—but historically part of Indian civilization)

- Gujarat and Maratha (West)

- Dravida (South)

- Utkala and Banga (East)

This geographic inclusivity was revolutionary for its time. The anthem doesn’t glorify war or kings—it celebrates the land, its people, and a guiding spirit beyond politics.

Common Misconceptions Debunked

- Myth: It was written for King George V.

Fact: No historical evidence supports this; Tagore denied it repeatedly. - Myth: The entire song is the national anthem.

Fact: Only the first stanza (5 lines) is official; the full song has 5 stanzas. - Myth: It replaced ‘Vande Mataram’ due to political bias.

Fact: The choice was made for inclusivity and secular unity in a pluralistic nation.

[INTERNAL_LINK:history-of-indian-national-symbols] Understanding these nuances is key to appreciating India’s symbolic heritage.

Why This Moment Matters Today

In an age of historical revisionism and online misinformation, revisiting the true story of Jana Gana Mana first sung is more important than ever. It reminds us that India’s national symbols were crafted with deep thought, inclusivity, and spiritual vision—not political expediency.

Every time the anthem plays—at schools, stadiums, or Olympic podiums—it echoes that winter morning in 1911 when a poet dreamed of a united India long before it existed.

Conclusion: A Song That Became a Soul

From a quiet invocation at a Congress session to the thunderous pride of a billion hearts, ‘Jana Gana Mana’ has journeyed far. Its first public performance on December 27, 1911, wasn’t just a musical debut—it was the birth of a national conscience. As we honor that legacy, let’s do so with truth, respect, and the same unity that Tagore envisioned over a century ago.