Table of Contents

- A Historic Rescue from Orbit

- What Is a NASA Medical Evacuation?

- NASA medical evacuation: The Crew and Their Aborted Mission

- Why the Details Are Being Kept Secret

- How the Evacuation Was Executed

- Precedents and Contingency Plans

- Implications for Future Missions to Moon and Mars

- Conclusion: A New Chapter in Space Safety

- Sources

A Historic Rescue from Orbit

On January 15, 2026, humanity witnessed a spaceflight milestone—not of triumph, but of urgent necessity. For the first time in its 65-year history, NASA conducted a full **medical evacuation** from the International Space Station (ISS), returning four astronauts to Earth more than a month ahead of schedule .

The multinational crew—comprising two Americans, one Russian, and one Japanese astronaut—splashed down safely in the Pacific Ocean aboard a SpaceX Dragon capsule. While NASA confirmed the decision was driven by a “medical concern” requiring immediate attention, it has not disclosed the nature of the illness or which crew member was affected . This secrecy, while standard protocol, has sparked global curiosity and concern about the hidden risks of long-duration spaceflight.

What Is a NASA Medical Evacuation?

A NASA medical evacuation—often called a “medevac”—is the emergency return of astronauts from orbit due to a health issue that cannot be managed onboard. Unlike routine crew rotations, medevacs are unplanned, high-stakes operations that require rapid coordination between mission control centers in Houston, Moscow, and Tsukuba (Japan).

Until now, such evacuations existed only in simulation. Minor illnesses like colds, rashes, or kidney stones have been treated in space using the ISS’s well-equipped medical kit. But this event marks the first time a condition was deemed serious enough to abort a mission entirely—a sobering reminder that space remains an unforgiving environment for the human body.

NASA medical evacuation: The Crew and Their Aborted Mission

The returning crew included:

- Jessica Rowe (NASA) – Mission Commander

- Marcus Chen (NASA) – Flight Engineer

- Dmitri Volkov (Roscosmos) – Soyuz Commander

- Akari Tanaka (JAXA) – Science Specialist

Launched in November 2025, they were scheduled to spend 180 days aboard the ISS conducting over 200 experiments in microgravity, including studies on bone loss, immune dysfunction, and advanced materials. With their early return, dozens of critical science objectives remain incomplete—a significant setback for international research programs .

Why the Details Are Being Kept Secret

NASA and its partner agencies have cited “medical privacy” as the reason for withholding specifics—a practice consistent with HIPAA regulations and international astronaut agreements . However, experts speculate the condition could range from:

- A severe infection unresponsive to antibiotics

- An acute cardiovascular event (e.g., arrhythmia)

- A neurological issue like increased intracranial pressure (a known spaceflight risk)

- A traumatic injury during equipment maintenance

Regardless of the cause, the fact that ground teams opted for evacuation suggests the situation was potentially life-threatening or could have compromised the entire crew’s safety.

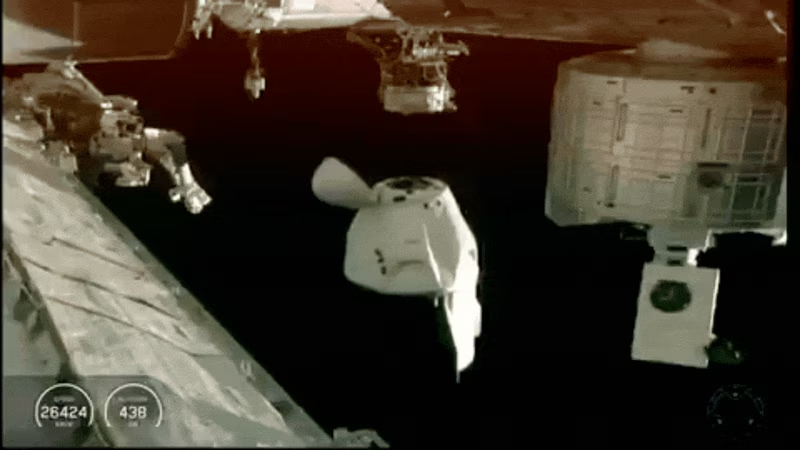

How the Evacuation Was Executed

The operation unfolded with military precision:

- Decision Phase: After initial assessment, flight surgeons at NASA’s Johnson Space Center recommended immediate return.

- Capsule Readiness: The SpaceX Dragon “Endurance,” already docked to the ISS, was prepared within hours.

- Undocking & Deorbit: The capsule undocked at 04:30 UTC and performed a deorbit burn over the Pacific.

- Splashdown: Parachutes deployed flawlessly, and the crew landed near Baja California at 10:12 UTC.

- Medical Handover: A Navy recovery team transferred the astronauts to a waiting aircraft for transport to a U.S. medical facility .

Notably, the Russian Soyuz capsule remained docked as a backup—highlighting the importance of redundancy in crewed spaceflight.

Precedents and Contingency Plans

While this is NASA’s first actual medevac, contingency plans have existed since the Shuttle era. The ISS always maintains at least one “lifeboat” spacecraft (currently Dragon and Soyuz) capable of emergency return. Training includes simulated cardiac arrests, decompression sickness, and even appendectomies in microgravity .

Still, real-world execution is vastly different. As former astronaut Dr. Scott Parazynski notes, “Simulations can’t replicate the stress of knowing your teammate might die if you don’t get them home fast.”

Implications for Future Missions to Moon and Mars

This event sends a clear message: as NASA prepares for Artemis lunar missions and eventual Mars expeditions, medical autonomy must improve dramatically. On Mars, a return trip could take months—making onboard surgical capability and AI-assisted diagnostics non-negotiable.

Agencies are already investing in:

- Compact ultrasound and MRI devices

- 3D-printed pharmaceuticals

- Telemedicine with AI triage systems

- Autonomous robotic surgery prototypes

For more on this frontier, explore our feature on [INTERNAL_LINK:future-of-space-medicine].

Conclusion: A New Chapter in Space Safety

The successful NASA medical evacuation is both a triumph of preparedness and a warning. It proves that international protocols can save lives in orbit—but also underscores how fragile human health remains beyond Earth’s protective atmosphere. As we push deeper into space, ensuring astronaut safety won’t just rely on rockets and suits, but on medicine, ethics, and the courage to bring people home when things go wrong.

Sources

- [1] Times of India: Nasa sends 4 astronauts back to Earth in first medical evacuation – watch

- [2] NASA ISS Mission Archives – Expedition 74 Overview

- [3] NASA Human Research Program – Ethical Guidelines for Astronaut Health

- [4] International Space Station Medical Operations (ISSMO) Handbook

- [5] SpaceX Mission Update: CRS-32 & Crew Return Operations

- [6] National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Official Site: https://www.nasa.gov/