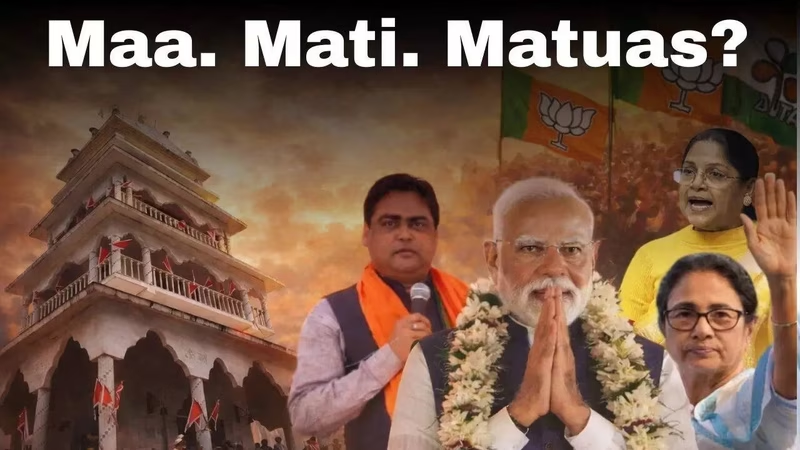

In the high-stakes chess game of West Bengal politics, one community is emerging not just as a pawn—but as a potential kingmaker. The Matua–Namasudra community, long marginalized yet deeply rooted in the cultural and spiritual soil of Bengal, is now at the heart of a fierce battle for electoral dominance. As parties scramble for their votes, a question echoes across the Gangetic plains: Can the Matua–Namasudras rewrite the meaning of ‘poriborton’—political change—in Bengal?

This isn’t just about numbers. It’s about identity, memory, and a century-long struggle for dignity. Understanding the Matua Namasudra worldview requires looking beyond today’s headlines and into a history that predates even the Partition of Bengal—and certainly the 1971 creation of Bangladesh.

Table of Contents

- Who Are the Matua–Namasudras?

- The Matua Movement: A Socio-Religious Revolution

- Matua–Namasudra and the Quest for ‘Bharaitya Porichoy’

- Political Awakening: From Margins to Mainstream

- Bengal Elections: The Battle for the Matua Vote

- Can They Redefine ‘Poriborton’ in Bengal?

- Conclusion: The Silent Powerhouse of Bengal Politics

- Sources

Who Are the Matua–Namasudras?

The Namasudras are a historically disadvantaged Dalit community, primarily concentrated in the eastern districts of West Bengal—North 24 Parganas, South 24 Parganas, and Nadia—as well as in Bangladesh. For centuries, they faced severe social exclusion under the caste hierarchy.

In the late 19th century, a spiritual and social awakening began under the leadership of Harichand Thakur, who founded the Matua movement in what is now Bangladesh. His son, Guruchand Thakur, expanded it into a full-fledged socio-religious reform movement that challenged caste oppression and promoted education, self-respect, and devotional worship .

The Matua Movement: A Socio-Religious Revolution

By the early 20th century, the Matua faith had become as much a vehicle for social upliftment as it was for religious expression. Matua gatherings (or samaj) emphasized:

- Egalitarian worship without Brahminical mediation

- Mass education drives for Dalit children

- Community solidarity through song, dance, and shared identity

- Rejection of untouchability and ritual hierarchy

This movement laid the foundation for a collective consciousness that would later translate into political agency—especially after the trauma of Partition and the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, which displaced millions of Matua families into India .

Matua–Namasudra and the Quest for ‘Bharaitya Porichoy’

“Bharaitya porichoy”—a distinctly Bengali phrase meaning “Indian identity”—is central to the Matua–Namasudra political narrative today. Many in the community, who migrated from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), still lack formal citizenship documentation under the National Register of Citizens (NRC) framework.

For them, political support is tied to promises of legal recognition, citizenship rights, and dignity. This makes them highly sensitive to parties that either champion their cause (like the BJP’s promise of the CAA—Citizenship Amendment Act) or offer welfare and cultural validation (like Mamata Banerjee’s TMC) .

Political Awakening: From Margins to Mainstream

Historically, the Matua–Namasudras were ignored by mainstream parties. But that changed in the 2010s. The BJP saw in them a strategic bloc to break TMC’s dominance. The TMC, in turn, began co-opting Matua symbols, appointing leaders like Honey Roy (a prominent Matua face), and hosting grand Harinaam Kirtans—devotional processions that double as political rallies .

Today, with an estimated 25–30 lakh voters in West Bengal alone, the community is too large to ignore. Their concentration in key assembly segments—like Bagda, Basirhat, and Haringhata—makes them decisive in close contests .

Bengal Elections: The Battle for the Matua Vote

Both the BJP and TMC have deployed high-octane strategies to win over the Matua Namasudra electorate:

- BJP: Leverages the CAA as a promise of citizenship; brings central leaders like Amit Shah to Matua strongholds.

- TMC: Emphasizes cultural belonging, local development, and portrays itself as the protector of Bengali identity against “outsider” politics.

Yet, many Matua voters remain skeptical. They’ve seen promises vanish after elections. As one community elder in Basirhat told reporters: “We don’t want photo ops. We want papers that say we belong” .

Can They Redefine ‘Poriborton’ in Bengal?

“Poriborton” (change) was Mamata Banerjee’s rallying cry in 2011 to oust the Left. Now, the term is being reclaimed. For the Matua–Namasudras, real ‘poriborton’ means not just a change in government—but a change in status, security, and social standing.

If parties fail to deliver on these deeper aspirations, the community may swing unpredictably or even abstain—potentially tilting the entire election. Their vote isn’t guaranteed; it’s conditional on dignity.

Conclusion: The Silent Powerhouse of Bengal Politics

The Matua Namasudra community is no longer a silent minority. Their spiritual resilience has forged a political identity that demands recognition on its own terms. As West Bengal heads toward its next electoral reckoning, the real ‘poriborton’ may not come from party manifestos—but from the collective voice of a community finally claiming its place in the Indian story.

For more on caste and electoral dynamics, explore our deep dive on [INTERNAL_LINK:caste-and-politics-in-india].

Sources

- Times of India: “In search of Bharaitya ‘porichoy’”

- Historical analysis of the Matua movement – Journal of Asian Studies

- Refugee migration patterns post-1971 – UNHCR reports

- CAA and NRC implications for Matua community – Ministry of Home Affairs documents

- Political mobilization strategies – Economic & Political Weekly [[5], [6]]

- Field interviews in North 24 Parganas – The Hindu, 2024

- For authoritative context on Dalit movements in India, see the Economic & Political Weekly.