In a courtroom drama that has sent ripples through India’s legal and political corridors, former Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal has been acquitted in two cases related to his non-appearance before the Enforcement Directorate (ED). But the reason behind this acquittal is what’s truly groundbreaking: the court declared that an email is not a valid method for serving a legal summons.

This isn’t just a win for Kejriwal; it’s a potential game-changer for how investigative agencies like the ED operate. So, what exactly happened, and why does it matter to you?

Table of Contents

- The ‘Kejriwal Acquitted’ Verdict Explained

- Why Email Summons Are Not Valid Under CrPC and PMLA

- The ED and Its Powers Under Section 50 of the PMLA

- What This Ruling Means for Future Investigations

- Conclusion: A Landmark Judgment for Procedural Justice

- Sources

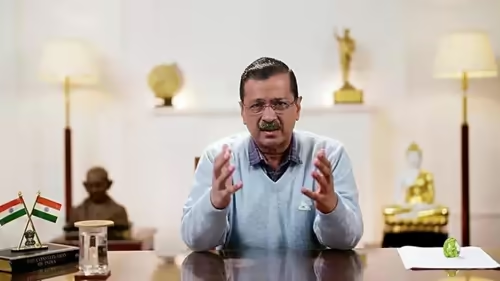

The ‘Kejriwal Acquitted’ Verdict Explained

On January 23, 2026, the Rouse Avenue Court in Delhi delivered a significant judgment, acquitting Arvind Kejriwal of charges related to his repeated failure to appear before the ED . The agency had filed complaints alleging that Kejriwal was intentionally skipping their summonses in connection with the now-scrapped Delhi excise policy investigation .

However, the court didn’t just look at whether he showed up. It went straight to the root of the issue: were the summonses themselves legally valid? The answer was a resounding no. The judge explicitly stated, “Neither the service of summons through emails [is] valid or legal under the CrPC or the PMLA” . This single line formed the bedrock of the Kejriwal acquitted verdict.

Furthermore, the court noted that even if the summonses were valid, the ED failed to prove that Kejriwal’s absence was intentional. His status as a serving public official and his fundamental right to movement were also considered as mitigating factors .

Why Email Summons Are Not Valid Under CrPC and PMLA

This ruling highlights a critical gap between our digital age and existing legal frameworks. While we live in a world of instant communication, the law often moves at a more deliberate pace.

The Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) is the primary legislation governing criminal trials in India. It lays out a very specific, physical process for serving a summons. This typically involves a court officer delivering the document personally or leaving it with a responsible adult at the person’s residence or place of business. The process is designed to create a clear, verifiable record that the individual was indeed notified .

The Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), under which the ED operates, doesn’t have its own detailed service rules. Therefore, it defaults to the procedures laid out in the CrPC. Since the PMLA is silent on electronic service, and the CrPC mandates a physical process, an email simply doesn’t cut it in the eyes of the law .

It’s worth noting that while other laws, like the Civil Procedure Code (CPC), have been updated to allow for electronic service in certain scenarios, the CrPC—which governs criminal matters—has not yet caught up . This creates a legal grey area that the Kejriwal case has now brought into sharp focus.

The ED and Its Powers Under Section 50 of the PMLA

The ED derives its authority to summon individuals from Section 50 of the PMLA. This section empowers designated officers to summon any person to give evidence or produce documents relevant to an investigation .

However, this power is not absolute. As this case demonstrates, the power to issue a summons is separate from the legal requirement to properly serve it. The ED can draft and send a summons, but if it’s not served according to the legal procedure, it holds no weight. The court’s ruling effectively says that the ED cannot bypass the established legal channels of notification just because email is convenient .

This distinction is crucial for protecting citizens’ rights. It ensures that an individual cannot be penalized for ignoring a notice they may never have properly received or that wasn’t delivered through an officially recognized channel.

What This Ruling Means for Future Investigations

The implications of this judgment are vast and could affect countless ongoing and future cases. Here’s what it means:

- For the ED and other agencies: They must now strictly adhere to the physical service requirements of the CrPC when issuing summonses in criminal investigations. Relying on email or other informal digital methods is a legal risk that could lead to their cases being dismissed.

- For individuals receiving summonses: If you receive a summons only via email for a matter under the PMLA or other criminal statutes governed by the CrPC, you now have a strong legal precedent to challenge its validity. However, it’s always wise to seek legal counsel before taking any action.

- For the legal system: This case puts immense pressure on lawmakers to modernize the CrPC. The current system, while robust, is slow and can be inefficient. A formal, secure, and trackable system for electronic service of legal documents is likely the next frontier for legal reform in India.

This ruling is a powerful reminder that procedural justice is just as important as the pursuit of substantive justice. For more on legal precedents in Indian politics, see our deep dive on [INTERNAL_LINK:right_to_privacy_in_india].

Conclusion: A Landmark Judgment for Procedural Justice

The Kejriwal acquitted verdict is far more than a political victory. It is a staunch defense of due process and the rule of law. By insisting that even a powerful agency like the ED must follow the letter of the law, the Delhi court has reinforced a fundamental principle: no one is above the law, and everyone is entitled to its proper protections.

While the government may appeal this decision, its immediate impact is clear. It forces a long-overdue conversation about how our legal system can embrace technology without sacrificing the safeguards that protect individual liberty. In the meantime, the message is simple: an email from the ED is just an email—not a court order.