Table of Contents

- The Quiet Genius and the Published Rival

- Newton vs Leibniz: How the Dispute Erupted

- Why Leibniz’s Notation Won the Long Game

- The Royal Society Scandal That Broke Trust

- What Historians and Mathematicians Agree On Today

- Conclusion: A Legacy Forged in Conflict

- Sources

The Quiet Genius and the Published Rival

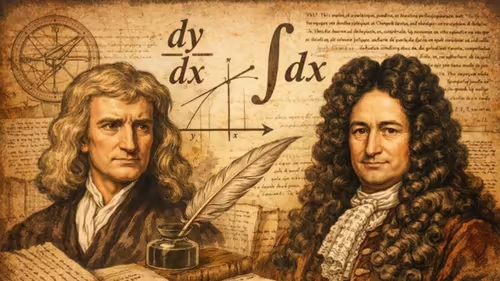

In the late 17th century, two of the greatest minds in human history were working on the same revolutionary idea—calculus—without knowing it. On one side was Isaac Newton, the reclusive English physicist who developed his version, which he called “fluxions,” during the plague years of 1665–1666 while secluded at his family home in Woolsthorpe .

On the other was Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the German polymath, diplomat, and philosopher, who independently arrived at his own system of calculus around 1675 and—crucially—published it first in 1684 in the scholarly journal Acta Eruditorum .

While Newton kept his work private for decades, sharing it only with select colleagues in manuscript form, Leibniz gave the world a clear, elegant notation (like dx and ∫) that made calculus accessible, teachable, and scalable. This difference would ignite one of the most infamous intellectual feuds in scientific history.

Newton vs Leibniz: How the Dispute Erupted

For years, there was mutual respect. Newton even wrote to Leibniz in coded letters describing his methods, and Leibniz acknowledged Newton’s early insights. But as calculus spread across Europe, national pride and academic rivalry took over.

By the early 1700s, British mathematicians began accusing Leibniz of plagiarism. The conflict escalated when John Keill, a supporter of Newton, publicly claimed in 1708 that Leibniz had stolen Newton’s ideas . Leibniz demanded a retraction. Instead, he got a full-blown investigation—one led by none other than Newton himself, who was then President of the Royal Society.

Key Events in the Calculus War

- 1684: Leibniz publishes the first paper on differential calculus.

- 1687: Newton finally publishes his fluxion-based methods in Principia Mathematica—but in geometric form, not algebraic calculus.

- 1704: Newton includes a detailed account of fluxions in an appendix to his Opticks.

- 1712: The Royal Society releases the Commercium Epistolicum, a report concluding Leibniz plagiarized Newton—written largely by Newton himself.

- 1716: Leibniz dies, isolated and disgraced in continental Europe, while Newton is hailed as Britain’s scientific hero.

Why Leibniz’s Notation Won the Long Game

Despite the scandal, history ultimately favored Leibniz—not because he “won” the feud, but because his Leibniz notation was simply superior for practical use. His symbols like dy/dx for derivatives and ∫ for integrals are intuitive, flexible, and visually suggestive of the underlying concepts .

Newton’s dot notation (e.g., ẋ for dx/dt) worked well in physics but proved clunky for more abstract or multivariable problems. By the 19th century, even British mathematicians abandoned Newton’s system in favor of Leibniz’s. Today, every student learning calculus uses Leibniz’s language—ironically, often without knowing his name.

This is a classic case where utility triumphs over national loyalty. For more on how mathematical notation shapes understanding, see our deep dive on [INTERNAL_LINK:evolution-of-mathematical-symbols].

The Royal Society Scandal That Broke Trust

The most damning chapter came in 1712. The Royal Society, under Newton’s presidency, appointed a committee to investigate the plagiarism claims. The resulting report, Commercium Epistolicum, declared Newton the sole inventor and accused Leibniz of deceit .

What the public didn’t know? Newton had secretly written much of the report himself and handpicked the committee members. When this was later revealed, it severely damaged the Society’s credibility and turned the dispute from a scholarly debate into a symbol of institutional bias.

Modern historians widely regard the Royal Society’s verdict as a miscarriage of justice—a product of ego, nationalism, and unchecked power rather than objective scholarship.

What Historians and Mathematicians Agree On Today

Today, the consensus is clear: both Newton and Leibniz invented calculus independently. They approached it from different angles—Newton from physics and motion, Leibniz from geometry and logic—but their core insights were equivalent .

The American Mathematical Society and leading historians of science, including those at the University of Cambridge, now credit both men as co-inventors. The real tragedy isn’t who was first—it’s that their rivalry delayed the spread of calculus in England for nearly a century, setting British mathematics back while continental Europe surged ahead .

As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy notes, “The priority dispute poisoned intellectual relations between Britain and the Continent for decades” .

Conclusion: A Legacy Forged in Conflict

The Newton vs Leibniz saga is more than a historical footnote—it’s a cautionary tale about how ego, secrecy, and institutional power can distort truth. Yet from this bitter conflict emerged a tool that powers everything from rocket science to AI algorithms. The next time you solve a derivative, remember: you’re using Leibniz’s symbols to describe Newton’s vision of a clockwork universe. And maybe, just maybe, give a silent nod to both geniuses whose feud changed the world.